How Native-owned tour operators can improve their sales without spending a fortune

Inadequate marketing, due to insufficient marketing budgets, are often cited as one of the most pressing obstacles for Native-owned tour operators in the United States. Especially as the tourism industry as a whole continues to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic. However, just because slim operating margins prevent your business from large scale advertising campaigns it […]

Native American Tours Turns 3!

It’s hard to believe, but it was just three short years ago that we decided to stop complaining about the need to boost Indigenous Tourism and start doing something about it. Native American Tours was born. It hasn’t been easy, but then again, nothing worth doing ever is. Helping Native tour operators increase sales through […]

An Unforgettable Indigenous Experience at the Grand Canyon

Grand Canyon National Park, with over 4.7 million visitors in 2023, is one of the most visited natural landmarks in the world. Yet, many tourists miss out on an extraordinary opportunity to experience Native culture and history while simultaneously taking in one of the Seven Natural Wonders of the World. Meet the Hualapai At the […]

NAT Respectfully Reminds Tourists to Please Hydrate this Summer

Native American Tours is the only booking software company in the United States owned and operated by Native Americans. As such, many of our clients are popular outdoor tours on Tribal lands. These tours offer visitors a glimpse of some of the most iconic, and most photographed, natural wonders in the world. However, they also […]

Learn to Code

While access to technology has long been a major obstacle for Native Americans, more opportunities are slowly arising that could allow for more Indigenous youth to pursue a career in web development, coding or AI. Native owned software companies, like Native American Tours, are looking to lead the way. The Challenge While there has not […]

Unconquered: The remarkable history and triumph of the Seminole Tribe

The story of the Seminole Tribe of Florida – the only tribe in America that has never signed a peace treaty – is one of the great Indigenous success stories in American history. Their strength, resilience and determination would form the foundation of the entrepreneurial spirit that defines them today. The Origins of the Seminole What is […]

Re-Discovering Monument Valley

Native American lands in the southwest United States offer some of the most popular tourist attractions anywhere in the world. Antelope Canyon, located within the Navajo Nation, sees in excess of 2 million visitors a year who come to witness one of the most photographed places on Earth. The Grand Canyon, located partially on Havasupai […]

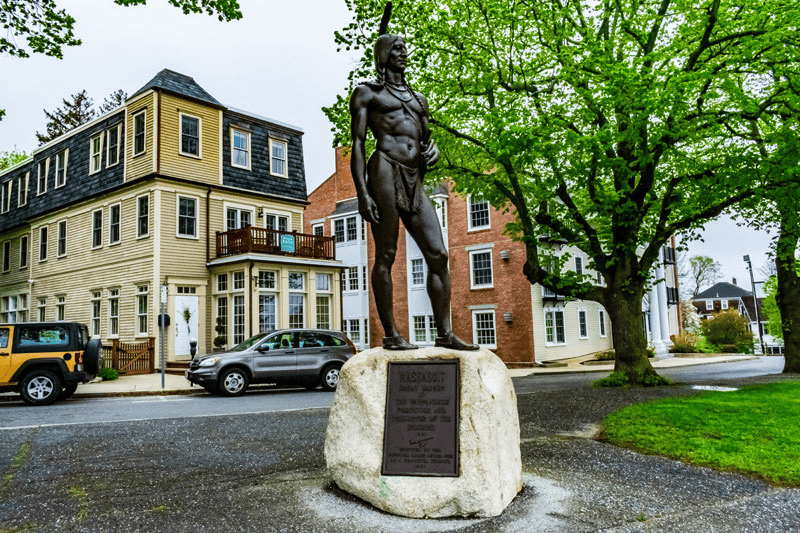

The Rich Heritage of Native New England

New England is one of the most abundant regions in the country when it comes to observing and preserving American history. Cities like Boston, Providence, Portsmouth, Lexington, and dozens of others feature countless homes, schools and churches that date back hundreds of years, in some cases 400 years. Visitors can immerse themselves in history, reliving […]

Indigenous Canada

In understanding and researching indigenous history, it is sometimes easy to forget that people lived and thrived throughout all of North America dating back to prehistoric times – not just within what is now the United States. That’s one reason Canada is often overlooked as a tourist destination for those seeking to explore and experience […]

Northern Rockies

Want to really get away? The vast Native American lands of the Northern Rockies are waiting for you Sometimes you just need a break. While visiting big cities, giant amusement parks or crowded events may seem like a great vacation to some, others need a vacation where they can unplug, take in the Great American […]