Perhaps nowhere else in the United States can you get a more in-depth look at Native American history than in one of the original “Indian Territories” itself – Oklahoma.

No less than 67 Tribal nations have called Oklahoma home, some of which date back as far as 14,000 years ago – the time of the last ice age. The long, storied history of Native people on this land is a history of overcoming grave injustices time and time again, rising from the ashes, and preserving their identities, their culture and their way of life against all odds.

The story of Native Oklahoma is in its own way, a uniquely American story – overcoming the countless government attempts to erase them from history to bear witness to the building of numerous museums and historical landmarks honoring and preserving that history today.

There is a piece of that history in every corner of Oklahoma, with no shortage of Native locals eager to share the story and traditions of their people with those who wish to listen. It’s why tourists come from all over the world to visit the Native cultural landmarks of Oklahoma and experience Native culture and history like nowhere else.

A brief history of Native Oklahoma

A millennium before Europeans arrived in North America, Native people were already flourishing in the land now known as Oklahoma. One of the most famous were the Spiro Mound builders, who were Caddoan speaking indigenous people of the prehistoric era. These natives created one of the most complex trade networks in the entire Americas, and had advancements in technology and governance that was considered far ahead of its time by historians. It is believed their political system controlled the entire region, which extended southeast as far as the Gulf of Mexico.

The Spiro Mound Builders in Oklahoma were likely ancestors of the Caddo and Wichita tribes we know today. Over the centuries many other tribes settled along the rivers, including Pawnee, Osage and Quapaw. Kiowa, Comanche, Arapaho and Apache would also move into the region and claim its fertile hunting and fishing grounds.

By the 1800’s, there were five dominant tribes in the southeast region of the US territories, who were described as the “Five Civilized Tribes” by colonialists – the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations. They were referred to as “civilized” because of their seeming acceptance of many aspects of European and American culture into their own – including horticulture, widespread adoption of Christianity, and a centralized form of government. The term was also used to distinguish them from other “savage” tribes who continued to rely on traditional hunting and kept to their customary religious practices.

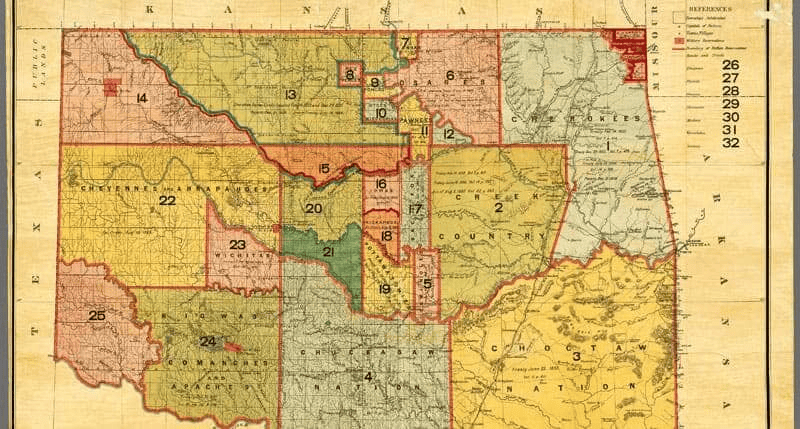

However, whatever peaceful co-existence that Tribal nations had with white settlers was abruptly shattered by the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which forced these and other tribes to relocate from their ancestral homeland to a newly established “Indian Territory”, which largely encompassed what is now Oklahoma, minus the panhandle.

At least half of the populations of the Muscogee and Cherokee died as they were forcibly uprooted and marched against their will over 2,000 miles under unbearable conditions to Indian Territory, a tragic chapter in American history known as the Trail of Tears. Once they arrived, they were forced to quickly learn to co-habitat with the tribes that already lived there, the aforementioned Apache, Arapaho, Comanche, Kiowa, Osage and Wichita. As years passed, other tribes were also forced from their homes to relocate to Indian Territory, such as the Kaw, Ponca, Otoe, Missouri, Alabama, the Delaware, Sac and Fox, Shawnee, Potawatomi, Kickapoo, Peoria, Ottawa, Wyandotte, Seneca, and Iowa. In all, by the end of the nineteenth century, 67 tribes were forced to call Indian Territory their new home, never to see their spiritual and cultural homelands again.

After the onset of the American Civil War, the tribes of Indian Territory were forced to enlist and fight – many for the Confederacy – as both the North and South fought for control of the region. In fact, one of the most pivotal battles of the Civil War was fought in Indian Territory – the Battle of Honey Springs, or the Affairs at Elk Creek as it is also known. The Union victory at Elk Creek denied the Confederacy of critical supply lines, and was later acknowledged as a turning point in the war.

However, after the Civil War ended, the Union retaliated against the tribes that were pressured to fight for the Confederacy, forcing them to sign the Reconstruction Treaties of 1866, which reduced their territory even further and allowed western railroads to be built across their land.

Over the course of the late nineteenth century, Oklahoma reservations for the tribes were finally created after hard fought battles during the Indian Wars. Then, just as the Oklahoma tribes had to persevere in the face of adversity and re-establish their traditional way of life amid their new environment after forced resettlement, they found themselves having to fight for their own cultural survival once again.

“Manifest Destiny” – the notion that the United States is destined by God to expand its reach across the entire North American continent – had firmly taken hold by the late 1800’s, as countless white settlers headed West. Rumors of gold, silver, cattle and other natural treasures soon followed and hundreds of thousands of outsiders were flocking to Oklahoma.

To make room, the Curtis Act of 1898, dissolved all formal tribal governments, ended reservation status and nullified tribal schools and judicial systems – a direct assault on Native rights and sovereignty. Soon after, Oklahoma declared statehood in 1907 and assumed all jurisdiction over all its territory, including Indian Lands. Indian tribes responded by demanding a state of their own, called the State of Sequoyah, but were simply ignored by Congress and the White House.

Despite all of these terrible injustices over the course of two centuries, despite continuously fighting attacks on their sovereignty and traditions, the Native people of Oklahoma persevered. Tribal governments still ran most tribes’ affairs, despite federal laws meant to disband them. The Indian nations did not disappear. Thanks to the development of their own written language, as well as storytelling by the elders through the generations, sacred customs and traditions were still observed and honored. Ceremonies continued to be practiced on a regular basis.

Despite being forcibly removed from their homeland, tribes adapted to their environments, and continued to live their lives by the sun, wind, earth and water as they had for centuries. No matter the hardships they endured, the indigenous people Oklahoma survived, as did their identity and way of life.

By 1936, the federal government had changed its policy with regard to Indian tribes, and Indian nations within the state of Oklahoma were reinstated by the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act. Over the coming decades, Oklahoma tribal members would become an indispensable partner to the Oklahoma economy, lifestyle and experience. Oklahoma tribes now employ over 96,000 people – most of them non-Native – through tourism and cultural events. In 2017, the latest year data is available, Oklahoma tribes produced nearly $13 billion in goods and services and paid out $4.6 billion in wages and benefits.

Today, the enduring spirit of the indigenous people of Oklahoma has inspired the creation of dozens of monuments, museums and landmarks to commemorate and celebrate Native Oklahoma. The collective experience of suffering and triumph, of rising from the ashes again and again, having to rebuild their culture over and over in new lands, all while continuously fighting to preserve their very way of life, has become an inspiration not only to fellow Oklahomans, but to people all around the world.

The incredible landmarks, beautiful Powwows and dances that are celebrated almost daily, and expansive Native museums that now populate Oklahoma are all a testament to that. A living testament that dozens of Native cultures that fought erasure and disenfranchisement for centuries are now firmly enshrined in Oklahoma for future generations to learn from and experience for years to come.

The best places to experience Oklahoma Native history

First Americans Museum

The First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City may be the most exhaustive project celebrating Native American heritage in the state. It is certainly the most ambitious.

Finally opened in 2021, construction for the museum began 15 years earlier in 2006 but was halted in 2012 when the initial $90 million in funds raised for the museum ran out and the state refused to pour any further money into it. However, the project resumed four years later when the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma agreed to partner with Oklahoma City to come up with the $175 million needed to finish.

However, tourists who have experienced the First Americans Museum – or FAM – will be the first to tell you the archaeological wonder is well worth the wait. Three decades of planning went into the launch of the 175,000-square-foot facility, and every aspect of the experience strives to be bigger, bolder and more interactive than any other Native American landmark.

National Geographic may have described it best:

“Most of the details in the museum’s architecture and interior reflect Native American influence. The stone wall leading to the museum’s main entrance represents the original inhabitants—the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminole—of Oklahoma. The 21st-century mound built around the museum pays homage to the prehistoric Mound Builder cultures and aligns with the cardinal directions. The 10 columns at the entrance symbolize the 10 miles Native communities walked along the Trail of Tears each day. Architects designed the Origins Theater to look like a giant piece of pottery traditionally made by the Caddo people.”

Central to the museum’s mission is to honor each of Oklahoma’s 39 nations, which represent more than 60 percent of all enrolled Native Americans in the U.S.

Okla Homma, the signature exhibition at the FAM in the South Wing, shares the stories of all 39 tribes in Oklahoma today through a highly interactive, multimedia exhibit in an 18,000 square foot gallery (the state’s name comes from two Choctaw words—“Okla” and “Homma,” meaning Red People).

Spiro Mounds Archaeological Center

For those who love to learn about ancient history, the Spiro Mounds Archaeological Center is a place you can’t afford to miss.

Once the seat of power during the Mississippian period (circa 800-1500 AD), the Spiro people employed a system of government and trade that dominated the region and an estimated 60 North American tribes. Now the only prehistoric American Indian archaeological site in Oklahoma open to the general public, tourists can take a step back in time – over a thousand years ago – and learn all about the burial mounds located in the area, discover the history behind the ancient artifacts that have been found here, and learn just how advanced this extraordinary civilization actually was for its time. The staff archeologist leads daily tours that explore how the Spiro people truly lived (one of the site’s most popular attractions).

The exceptional art, relics, artifacts and of course tombs found in the area were so numerous and historically significant they have since been nicknamed the “King Tut of the Arkansas Valley” signifying one of the great discoveries in archaeological history. To view and learn about these artifacts and history up close is simply an experience no aspiring history buff should be without.

Cherokee Heritage Center

In eastern Oklahoma, the Cherokee Heritage Center near Tahlequah will give visitors a unique look at Cherokee culture and history through interactive exhibits that celebrate every era of Cherokee existence.

Throughout the site’s 44 acres, you can visit a 1710 Cherokee Village called Diligwa, which provides an excellent showcase of the Cherokee way of life prior to the arrival of European colonists. There is the Adams Corner Rural Village, which depicts a Cherokee community and life during the 1890s with a 19th century church, schoolhouse and log cabin.

There is a powerful Trail of Tears exhibit, which takes the visitor on an emotional tour of the forced removal of the Cherokee, as told through artwork, life-size sculptures and historic documents in six galleries.

The center’s Cherokee National Archives house an impressive collection of important Cherokee historical records, including 167 manuscripts, 579 historic photographs, and 832 audio holdings. Visitors can also explore their own Cherokee heritage at the Cherokee Family Research Center.

Gilcrease Museum

History buffs and tourists seeking the immersive Native experience often gravitate towards museums and ancient cultural landmarks, but for those who truly appreciate Native American art, the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa is the place for you.

Home to one of the world’s most comprehensive collections of American Indian and Western art, the museum attracts artists and art aficionados from around the world. Artwork from Native cultures throughout the country are on display within the site’s 475 acres protected acres. Whether it is handcrafted rugs, jewelry, beadwork or pottery, the renowned artwork – from both modern times and ancient – offers one of the best ways to learn, appreciate and experience Native culture and heritage.

Five Civilized Tribes Museum

The Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muskogee, as the name suggests, is home to some of the most well-preserved historical artifacts of the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Creek, and Cherokee tribes anywhere in Oklahoma.

The building itself is a historical landmark, as the first Union Indian Agency building to house the Superintendence of the Five Civilized Tribes. Now converted into a museum, it seamlessly is able to convey the extraordinary culture and rich heritage of these tribes.

Visitors will not only experience well preserved artifacts from Oklahoma centuries ago, as well as traditional artwork and sculptures, but will also include historical documents and artifacts from their ancestral homelands prior to being forcibly relocated to the Indian Territory. Like many Native cultural sites, the Trail of Tears has a prominent role at this museum, as it should. It is a dark chapter in American history that should never be forgotten.

As told through artifacts and art, visitors get a true sense of the proud history and culture of these five tribes, both prior to first contact with white settlers, and after – including after incorporating some elements of Western culture into their own (hence the “civilized” moniker given to them by many in the US government).

Traditional art produced by artists of all five tribes adorn the gallery walls, and also proudly features many of the most prominent Native artists of modern times. Artists such as Willard Stone and Enoch Hane. The museum also has the world’s largest collection of Jerome Tiger originals, including Stickballer, his only major sculpture, which is on permanent display.

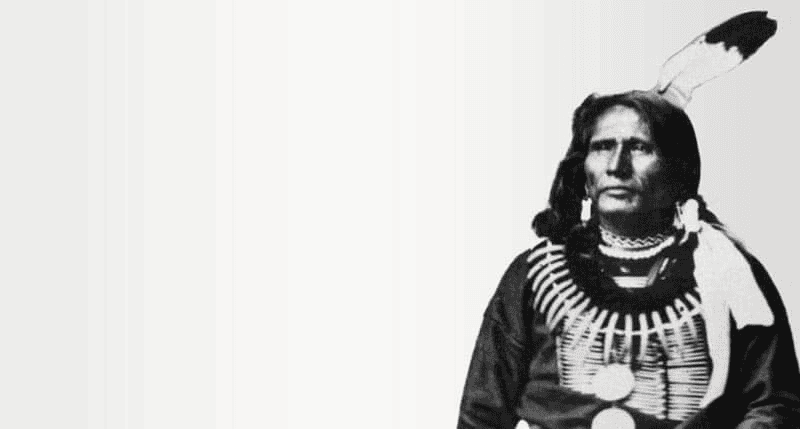

Standing Bear

The story of Chief Standing Bear is quite extraordinary.

Wanting to honor his son’s last wish to be buried in the Ponca homeland and not in the new land they were forced to relocate to (Indian Territory), Chief Standing Bear gathered a few members of his tribe and traveled north through the Great Plains until arriving in the Ponca lands they had previously known. Standing Bear buried the bones of his son along the Niobrara River.

However, because Indians were not allowed to leave their reservation without permission, Standing Bear and his followers were labeled a renegade band and arrested by the US government. With the help of a local newspaper, Standing Bear secured legal counsel and sued, challenging the federal government’s contention that he and his tribe were not a “person” under the meaning of the law.

At his trial, Standing Bear uttered this now famous quote, which still resonates today: “This hand is not the same color as yours but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be the same color as yours. I am a man. The same God made us both.” The U.S. District Court in Omaha ruled in favor of Standing Bear, saying he was in fact a “person” under the law, free to enjoy the rights of any citizen, including the ability to travel away from his designated territory.

Today, a visitor can pay tribute to Chief Standing Bear by visiting the 63-acre Standing Bear Park in Ponca City. There are walking paths among six tribal viewing courts, a small museum and an awe-inspiring 22-foot bronze statue of the Ponca tribal leader himself.

The inter-tribal Standing Bear Powwow takes place adjacent to the park each September, with native music, singing, dances and traditional food of the six area Native American tribes: Osage, Pawnee, Otoe-Missouria, Kaw, Tonkawa and Ponca.

Chickasaw Cultural Center

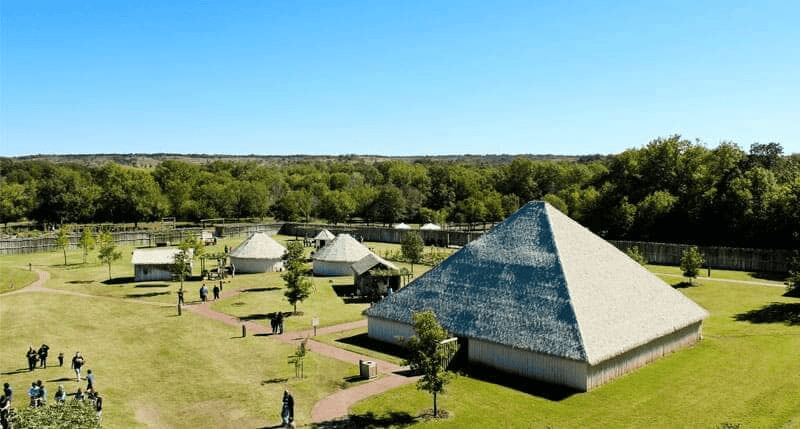

Located in the cultural center of the Chickasaw Nation, the 100 acre Chickasaw Cultural Center in Sulphur is widely considered one of the most intensive and interactive Native American experiences in the state.

Ten years in the making, the cultural center hosts reenactments, performances, historical collections, exhibits, classes, and special events. The Center allows visitors to see, feel and even taste the heritage of the Chickasaw tribe through interactive exhibits, botanical displays and traditional dwellings. There is even the opportunity to enjoy traditional fare such as grape dumplings, Indian fry bread and pashofa (a corn soup).

Tourists can journey through the Removal Corridor to get a true sense of the painful journey that brought the Chickasaws to Oklahoma through the Trail of Tears. The Center also include the Aaholiitobli’ (“a place to honor”) Honor Garden of native plants that honor the Chickasaw leaders, elders, and warriors; the Kochcha’ Aabiniili’ (“a place for sitting outside”) Amphitheater; and the Aba’ Aanowa’ (“a place for walking above”) Sky Pavilion, which offers a 40-foot birds’ eye view of the Chikasha Inchokka’ Traditional Village and the surrounding Chickasaw National Recreation Area.

Choctaw Nation Museum

Tuskahoma, an unincorporated community in northern Pushmataha County, Oklahoma, was the former seat of the Choctaw Nation government prior to Oklahoma statehood. Today, the small town (population 73) is home to the newly-restored Choctaw Nation Museum, which was the original 1884 capitol building for the Choctaw Nation.

The museum has an extraordinary collection of Choctaw art, exhibits, and artifacts, as it tells the nearly 14,000-year journey of the Choctaw people. Learn about what they endured during the Trail of Tears, the service of Choctaw Code Talkers and all about their culture and traditions today.

During Labor Day weekend, the Choctaw Nation Museum holds the Labor Day Festival and Inter-Tribal Pow-Wow, which is open to the public.

There’s much, much more

Other Native American cultural sites to consider visiting include the Citizen Potawatomi Nation Cultural Heritage Center in Shawnee; the Ataloa Lodge Museum in Muskogee; the Southern Plains Indian Museum in Anadarko; and the Museum of the Great Plains and the Comanche National Museum and Cultural Center, both in Lawton.

In all, there are more than 90 Native American attractions in Oklahoma. You could literally stay in Oklahoma for months and still not experience all the Native history, ceremonies and traditions the state of Oklahoma has to offer.

You simply have to visit for yourself.